Terms for your understanding:

Tico/a: someone from Costa Rica, i.e., the country where I’ll be living for the next two months.

San José: the capital of the aforementioned country, where I will spend the next two months in a homestay.

“Pura vida”: the aforementioned country’s unofficial motto, slung around like “Roll Tide” as a response to most everything. Literal translation: “pure life.”

Louisiana is flat. (Llano: a word I recognize from Borges’s Argentine landscapes.) Flat and low: Lafayette, my hometown, is 11 m above sea level. San José? More like 1300 m, and surrounded by mountains.

The mountains are the thing that strikes me most. Maybe my flat Louisiana mind is no good for comprehending these heights, where, in the distance, clouds rise from forests dotted with houses.

These are houses which, according to my host father (mi papá Tico), didn’t exist when he was a child. But that was in the 50s, and we had better call him my host grandfather, for apart from his wife and three of his adult children, his home also houses itinerant grandchildren. The house is small and redolent of the four generations of life it has provided for. It reminds me of my maternal grandparents’ home, where we used to go on Sundays when I was a child (the 2000s, 2010s). My abuelo Tico reminds me of my mom’s dad.

This man loves to talk. (“Muy habletín,” as he himself put it.) After serving breakfast or dinner to me and my roommate, he will stand nearby, his hands behind his back or else gesticulating, regaling us with stories and opinions about things current and past. Recent topics of conversation have included: a recent malfunction in the digital records system across Costa Rica, the “dictador” in Nicaragua, his forty-plus years working in the Caja Costarricense de Seguro Social, his penchant for gardening, car thieves, local fruits, insurance scams, San José’s awful traffic, the perfect grades his children used to get at the school standing across the street (an excellent landmark for a directionally challenged person like me), the “muchacha” from North Carolina who stayed with them years ago and cooked delicious food…

He loves to talk; I love him for it. His conversation at breakfast, with a little “cafecito” in a “Virginia Is for Lovers” mug, is what starts my day. I awake a bit earlier than my 7 am alarm, roused by the sun and the noise of the street and the school (children playing, sirens for recess that sound like ambulances—another thing my abuelo Tico spoke on). I come down from the separate upstairs suite (two bedrooms, one bath) whose emptiness originally prompted my hosts to start rooming international students some ten years ago. Then, breakfast, cafecito, conversation—well, before breakfast I tend to use the restroom. And again after breakfast… Maybe once more before I leave for school. My guts, like my head and my heart, need time to adjust to this place.

But after breakfast: free time. For the next four weeks I’ll be taking two classes in the afternoon: Latin American Dialectology, and Contemporary Costa Rican Women Writers. This leaves my mornings free to do homework—homework for the same day’s classes. (What scholarly liberties I take here!) Around noon I pass through our barrio, which I have almost gotten to know now, and I cross a street to another barrio, where Universidad Veritas is. (Crossing the street reminds me of crossing the street in Guangzhou. My father knows what I mean: I promise I’m being careful, Dad!)

Veritas is laid out interestingly. The main building is partially open-air, its main entrance like a garage that continues directly into the halls, where sunlight may peep in through a gap in the roof to warm a tree growing up from the floor. This airflow doesn’t stop me from donning my N95 as I enter; high-quality masks are required in classrooms, and I worry for my older hosts. Yet the tight mask, the morning heat, the long pants they said I’d have to wear (no shorts they said, but in practice you can spot an international student based on how much skin they show, and how light that skin is!)—it all makes for intense sweating.

Readers, I sweat here often, and much. (Yet for all this my acne is not as bad as I feared.)

After sweating (and, I confess, nearly swooning—for I have been tired) through my classes, I may hang out with new friends. I may attend a university event. The other day we watched short films on the theme of bodies and then drew with live models. Most likely, maybe, I will take the 5:10 shuttle home, to make it in time for dinner. (As opposed to the 6:10, 7:10, or 8:10 shuttles, all useful in the evening, when it rains, and when one shouldn’t walk around alone—especially carrying around an iPhone, indication to thieves that one is a gringo, and so, they think, a carrier of mucha plata). Dinner is like breakfast, but more of the family is there to assist in my abuelo Tico’s conversational labor. The TV is often on: there are programs about local Costa Ricans, or soccer matches, or Wheel of Fortune in Spanish (it’s not the game you know, Lindy, though my abuelo Tico shares your dream of being a contestant). Or news—most often it is news: flooding in certain provinces, the election in Colombia, the war in Ukraine, the shooting in Uvdale…

My Spanish is not good enough to understand everyone, or to let me express myself quickly and grammatically. But the other day I commented to my host family that news seems universal, cross-cultural: it’s always bad. “Las noticias siempre son malas.”

And this is a universal shame, because the world is sometimes—often—good. In Costa Rica, as in the US. But I know that I have been lucky. In this world, as the foundational Costa Rican author Carmen Lyra emphasized, people have been pulverized by poverty, sickness, the thoughtless greed of others… In this world, years ago, my abuelo Tico once met a Nicaraguan standing alone at the bus stop. He asked him why he didn’t talk; the man said that, in truth, he didn’t even eat. Sometimes he had a banana and a glass of water a day, and when he saw something he wanted to buy, he never would—so he could save money to send back to his family…

For perhaps no good reason, I have been lucky. And that there should be good things, even when there is so much wrong: before this fact I am reverent, perplexed, and small, as before mountains…

I excuse myself from dinner around 8. I shower: my roommate and I haven’t figured out how to turn the water warm, but in this heat and humidity, the cold is welcome. I may crank open the window to keep the mirror clear, but that risks letting in bugs of all sorts. (A spider, a fly, and fat black ants: I’ve shared my room with these.) I go to sleep around 10 or 11; ostensibly, I read Cien años de soledad before bed. My beloved high-school Spanish teacher gave me that years ago. (Señora Yoly, gracias, por todo.) I was afraid to begin it, but, emboldened by having recently read Don Quijote, and immersed now in Spanish, there is no better time to start.

But readers, there is so much more to say. And perhaps I’ve said things that aren’t even true—after all, how can I pretend to give you a “day in the life,” when I’ve been here less than a week? But who can avoid imposing structure on their experience, narrativizing it? Making meaning out of it?

In the context of all things, it may be frivolous, but I’m writing this on my iPhone on a bus to Punta Leona, that is, to the beach. I’ve met a fellow student from California; maybe he can teach me how to surf. I’m sure to look ridiculous, but after all, even down by the coast, the mountains shall be on my mind. So I can’t help being a little out of place.

Certainly, I can be silly here.

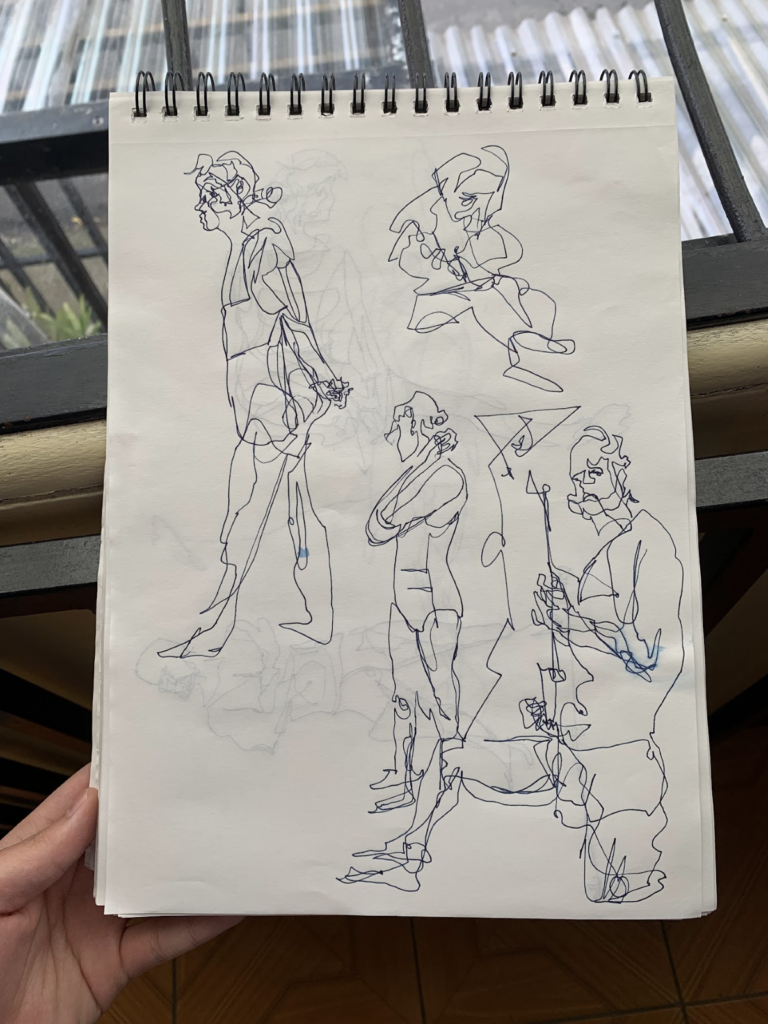

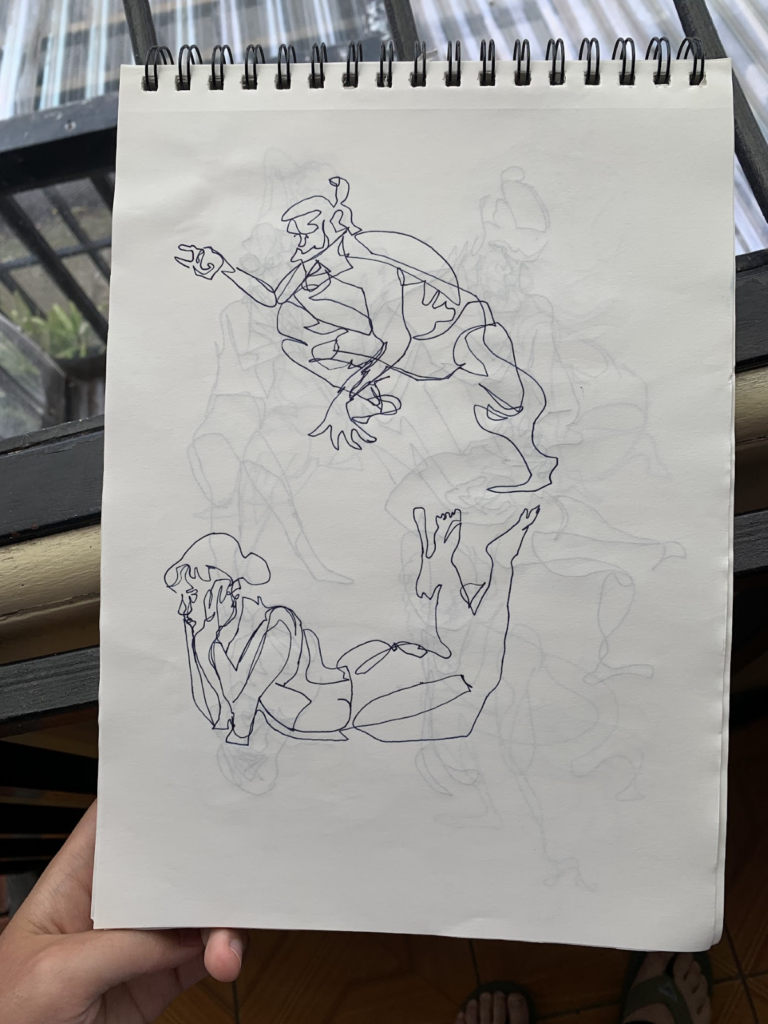

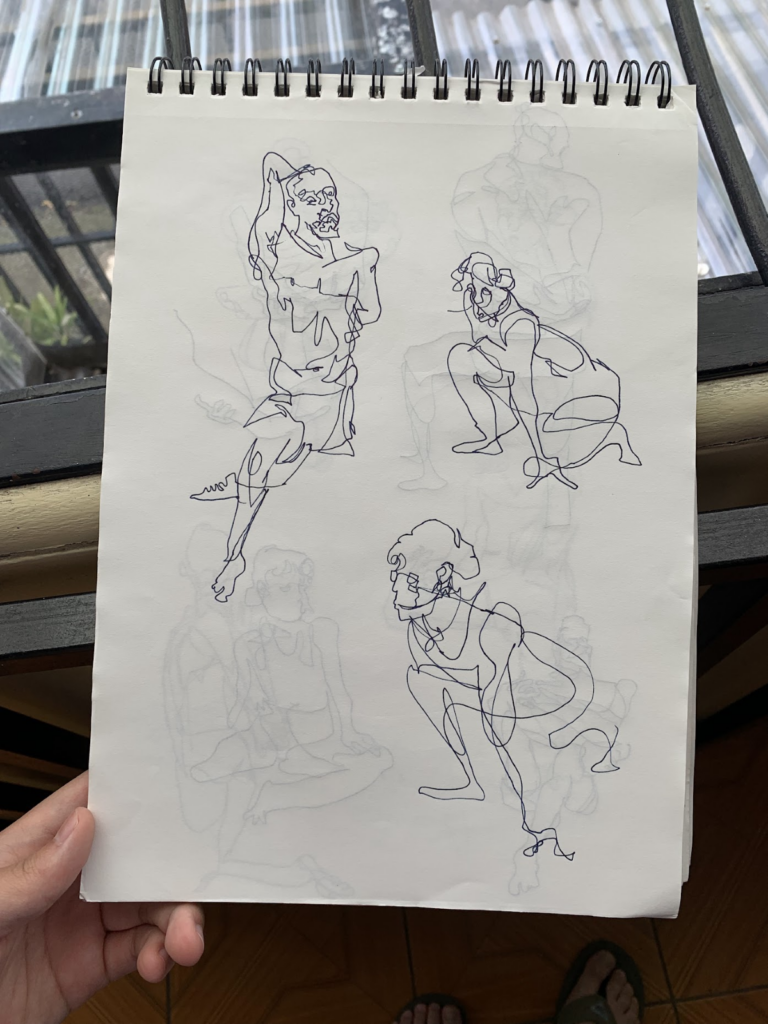

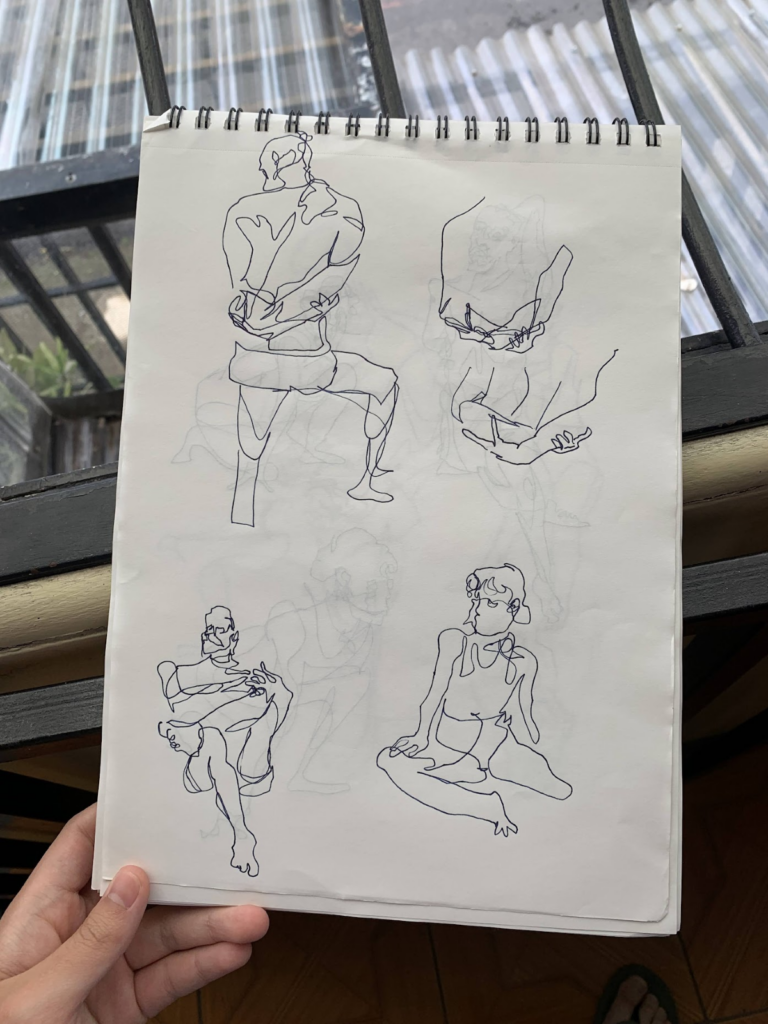

PS, Here are some of those drawings of live models. The man looked quite used to modeling. His forehead could have made him seem stern, but he didn’t seem unkind. The woman seemed less experienced: she often adjusted her poses, looked around the room, made eye contact, sneezed… she was wearing braces.