In Costa Rica, there are many ways to get wet. Hay varias maneras de mojarse. I don’t think I’ve spent a single day here totally dry; the main moistening agent has been my own sweat. Some days I can start the fifteen-minute walk to the university feeling fresh and cool, but by the time I’ve climbed that last hill before getting there, my back is inevitably slick with perspiration. Donning my N95 right after means sweating even more, my hot breath nourishing beads of moisture that dangle from the tip of my nose…

…But, readers, I’ve already told you about that. Enough with the bodily fluids. You’d probably rather hear about the beaches.

As you might expect from a country touching two oceans, Costa Rica has many beaches. The Caribbean coast is contained within the Afro-influenced province of Limón, while the Pacific coast is shared by the provinces of Guanacaste and Puntarenas. This last province is the only one whose beaches I’ve been to, so far. Puntarenas, which is my abuela Tica’s home province and whose shape on the map reminds me of Chile or of gerrymandering, has been the site of my first and third weekend excursions so far.

That first weekend, my program brought us to Punta Leona, a resort with two beaches located in what I can only describe as the jungle. The bus windows fogged up with condensation as we went up and down hills totally covered by vegetation. Discovering the resort in the midst of the forest gave me a sense for how a town, or anything else, could be hidden from the rest of the world in such a place. (I have been reading, finally, Cien años de soledad.)

One of the beaches was public, the other, private. Upon visiting the former right after arriving, I think I remarked that I hadn’t been to the beach since before the pandemic. But that’s not right – I remember Virginia Beach, Grandma Cindy. Anyway, my companion from California found that hard to believe. This is the one who, as it turned out, did not teach me how to surf, for there were no surfboards at either beach, though there was a good bit of garbage on the public one. Still, the sight of the jungled cliffs rising out of the water in the distance amazed me, prompting me to compare it to being in an Uncharted game. (See the picture above.) As vapid or naive a remark as they come, perhaps, but it is what came to mind.

That was Friday; the day after we visited the private beach, where the sands were white and hot. The sun was intense; I believe the UV index was “extreme,” and despite my best sunblocking efforts, I contracted a burn right above my upper lip that dried up and, later, prevented me from smiling without cracking it. Or maybe that was caused by the salt water that buffeted me as I bobbed amid the waves… (They warned us, incidentally, about riptides; I haven’t had to try it yet, but when the day comes, I know not to fight the current. You’ve got to conserve your energy…)

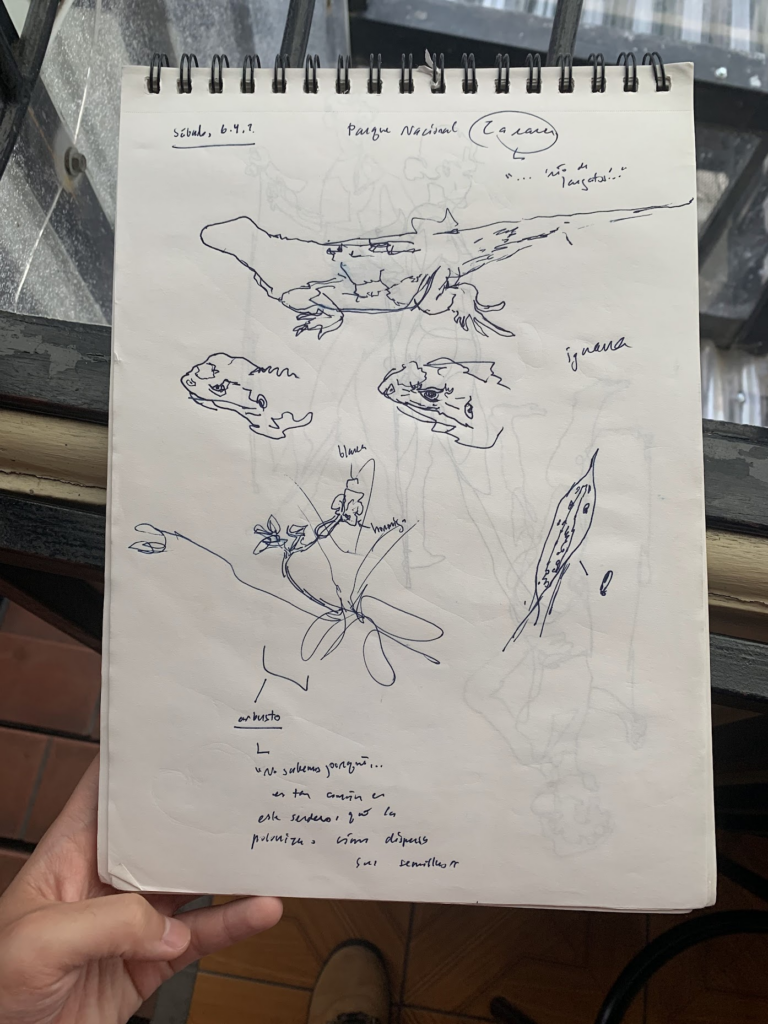

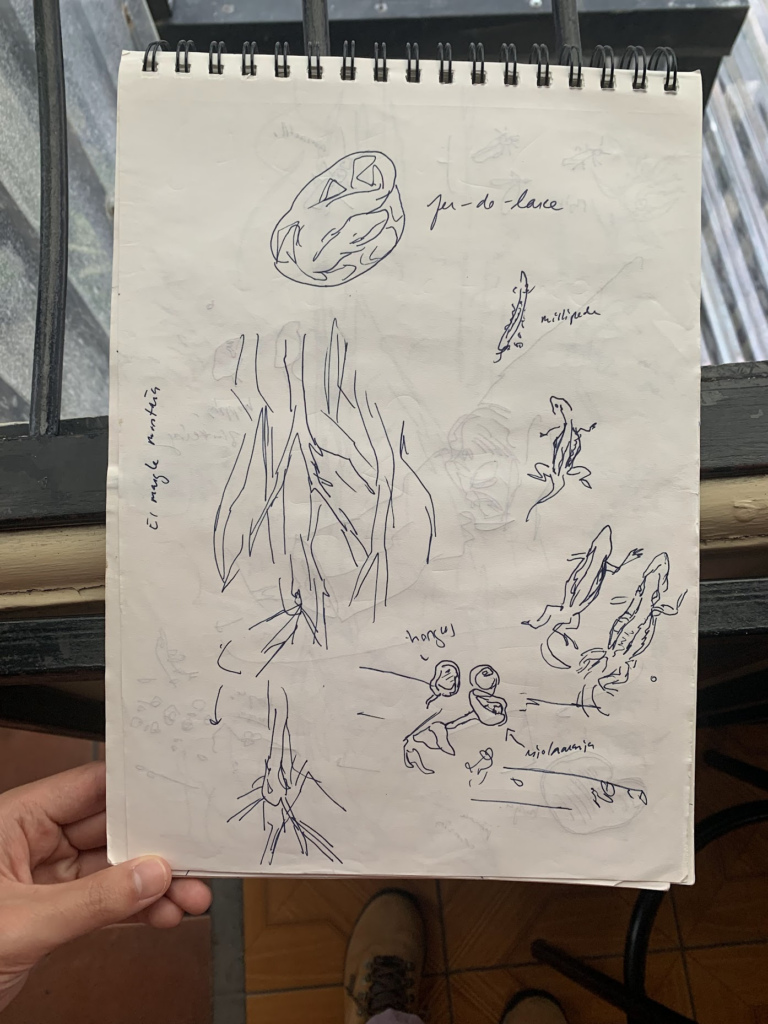

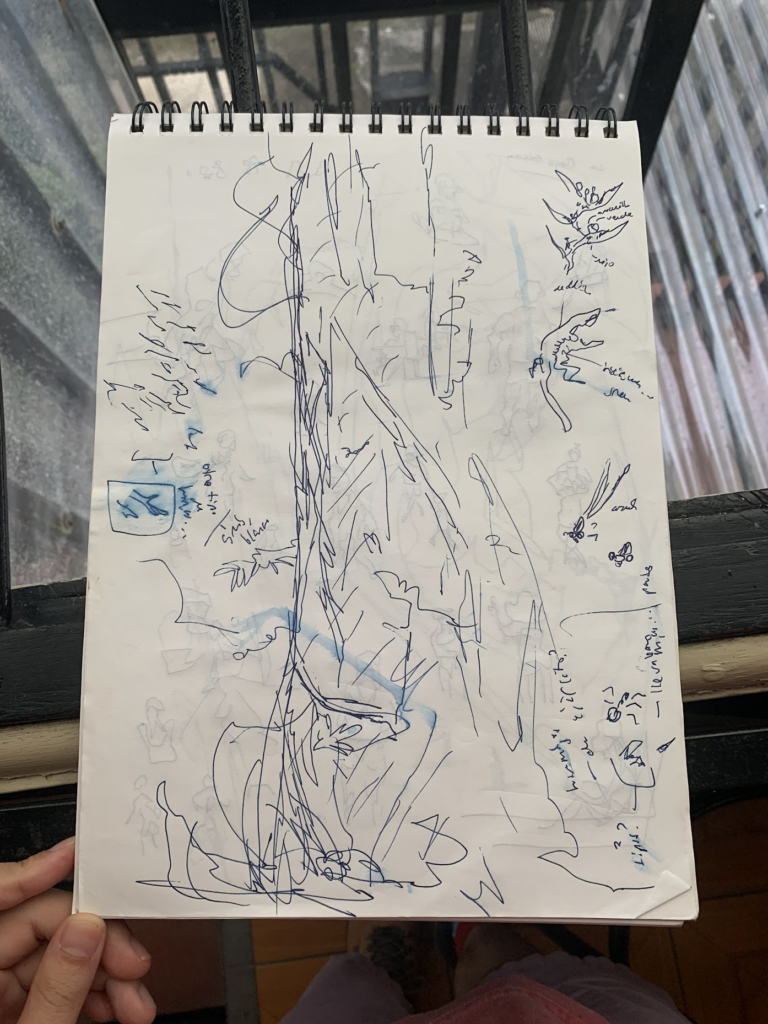

But there’s occasion again to talk about my sweat. Saturday morning we spent in Carara National Park, where we were greeted by an iguana in the parking lot, harbinger of many lizards, insects, and birds to come in the rainforest. (But no monkeys, as far as I could tell. Yet others saw them.) We entered and I quickly separated from my group to stop and sketch the life forms around me — the trees, the curious flowers and bushes, the strange funguses sprouting from the many rotting tree trunks…

Coiled near a tree there was a fer-de-lance; I contributed to public safety by scrawling “CAUTION FER-DE-LANCE” on one of my sketchbook pages, as directed by a responsible local, making a sign out of it. (I wonder how fast it decomposed in that heat and moisture…)

But as I was saying: the sweat. Sweat and blood (but no iron): my romp through Carara was the most I’ve sweated here so far, and that is saying quite a lot. But I was more concerned for my blood, for, having forgotten to purchase bug spray, I was assaulted by mosquitos the whole time I was there. To quote my tour guides’ diagnosis: me comieron vivo.

Suffice it to say that I bought bug spray on Monday, and applied it diligently on our next excursion the following weekend. The first attraction of that trip was the best: after descending 800 or so stairs (my guess) into the jungle, we got to swim in La Fortuna waterfall — or rather, around it, for it was forbidden to swim right underneath it. (I think people have died like that.) Not that anyone got too close; of the large crowd gathered there, many didn’t even get in the water. They stuck to the non-submerged rocks, which might have been wise, since the waterfall and the stream it drained into possessed a powerful current, which, as I discovered, was treacherous when combined with the half-submerged rocks I had to scramble across in order to maneuver around. I escaped with just a slightly bruised shin, but it could’ve been worse.

But the waterfall was a lovely time. It has been, so far, the most refreshing way to get wet in Costa Rica: the water was cool and clear, and the cascade generated a refreshing mist that I found much more paradisical than the heat at the beach. The next day, however, I was back to sweating, as we embarked on a steep morning hike to catch a view of the Volcán Arenal, a volcano I remember reading about in the Costa Rica chapter of a Spanish textbook. It erupted in the 60s, destroying its surroundings and killing many; my abuelo Tico remembers going there and seeing the glowing lava. But we didn’t see any; we didn’t see the volcano at all, for it was obscured by clouds. But as we began to descend from the observation point (which was, apparently, the original location of our hotel before the volcano erupted), I hopped a little barbed wire fence and got a nice view of the valley standing on top of a water collector… or something.

I washed off the sweat with a shower and hit the swimming pool. There’s another, more artificial way to get wet in Costa Rica. (Let’s put it in a similar category with the showers, which are rarely warm here. But I’ve already mentioned that.) I spent part of the first evening at Punta Leona bobbing on my back in a pool of what tasted like rainwater, staring up at jungle trees overhead. At the hotel near Arenal, I took many a trip down a water slide that twisted, turned, and then shrouded me in darkness right before spitting me out into the pool, stinging my back upon impact.

But the next weekend, when I returned to Puntarenas, I got stung worse — by jellyfish, or, at least, fragments of one. After crossing an early morning ferry across the Nicoya Bay, we had stopped at our little hotel in Paquera (a city my abuelo Tico later insisted is famously muy fea), and then headed to the Curú wildlife preserve where we were to spend the day. The beach there was the nicest I’ve been to so far, a massive stretch of dark sand opening out from the mouth of the rainforest, sloping gently out into a small bay.

The forest and the beach were populated with crabs of all sorts, not to mention the fish, corals, and sea urchins we got to see while snorkeling the next day. The water was rather murky then, owing to the torrential rain that had prevented us from snorkeling the day before. (We were supposed to snorkel at night amid bioluminescence; we didn’t.) However, I still spotted the aforementioned creatures – but no jellyfish. Rest assured, readers, that they were there, at least in part (in fragments). Others got stung that day, but I had gotten my fill of nematocysts the day before, when, at one point, I pulled a sticky tentacle off my wrist which left welts rivaling the mosquito bites from Carara. They don’t make jellyfish repellent. (Nor cat repellant; that evening a little cat wandered into the hotel restaurant and nipped me, which I find unjust, since I have found myself much more cautious around random cats and dogs here than my friends. Yet fortune is blind. Rest assured, readers, that I was told not to worry about rabies. COVID, hepatitis, typhoid: but I didn’t get that vaccine.)

Ah, readers! That, in short (very short), is the story of my three weekend excursions so far. I write this on my iPhone as we head off for a fourth one in Limón. (And I return to edit it on my iPhone on the way back. I’ll tell you about Limón another time. Just add corals to the list of animals that have attacked me here – better than those stingrays I suppose.) Most of my peers are here for only five weeks, which has given them, I think, a fever for excursions. If it were up to me, frankly, I’d have taken a weekend off by now – my mind, my spirit, and my wallet need a rest!

Which is to say that I have done a lot here already. There’s more to tell you. Would you like to hear about the jubilation in the streets that I took part in when Costa Rica qualified for the World Cup? (Or the hour I spent afterward wandering San José, lost, trying to get back to class?) How about the soccer match I attended in-person at the coffee-bean shaped Estadio Nacional? Or those tropical dance classes, where I’ve been sweating through the embarrassment and strange loneliness of feeling helpless, out of my element, moving my feet and arms and all the rest in ways that, surely, don’t correspond precisely to the salsa or bachata we were being taught, but that certainly, I believe, embody a joy that I am learning to move within…?

And then there’s the first night in Punta Leona, when I sang karaoke with one of the girls I came with (have I mentioned that there are only three boys in our group?), and then with my roommate. The first song was my pick: “Rosas,” by La Oreja de Van Gogh. The second, my roommate’s: “Body Like a Back Road.”

Readers, I think I am having fun.

PS. I almost forgot to make something (more) out of this post’s title. If you haven’t yet realized, I’ve been thinking a lot lately about time. I think the movement of time, and its structure, and our experience of memory, and of intention and prediction and those other dynamic, temporal things by which we live, are all subjects adjacent to the fundamental mystery and meaning of human living… (In this account of things, I can’t leave out the question of death, which, as I was telling my abuelo Tico this morning, is the indispensable subject of much of classical philosophy – how do we learn to live, knowing we will die? Or, how do we learn to die? My abuelo Tico mentions people who have died often. Though Ticos live for a long time, one doesn’t reach his age without attending some funerals. Yet he is not terribly old. Nor does he strike me as a man afraid of his own death…)

…On the trip back last weekend, I gazed out at the road, one of my favorite things to do on trips and in general. I recognized the same sights we saw coming back through Puntarenas two weekends before. Repetitions like that – but with variations: this time it was at night – are important. I reflected on the joy of these excursions, which lies not, principally, in what I do during them. Snorkeling in murky water, sweating buckets climbing a hill, exposing myself to an armada of mosquitos, or jellyfish fragments, or the ultraviolet radiation of the sun… But all of this under the aegis of the excursion. An excursion gives you a different kind of time to move in. It releases you from the anxious time of the work week, when you worry about getting things done, when time becomes less of a free movement of possibilities, and more of a static structure to be controlled and managed: what can I get done this day, at this time, and how, and so on… In the time of excursions, I am reminded that moments can, sometimes, simply come one after the other, each one fresh and curious like a surprise, like something I can experience in its own time. These are moments which, though I did not try to predict and control them, I know I shall remember with sweetness and translucent clarity…

…And life is also its own excursion, through its own jungles, and beaches, and cities, and these teeming with people, who are both strange, and knowable.